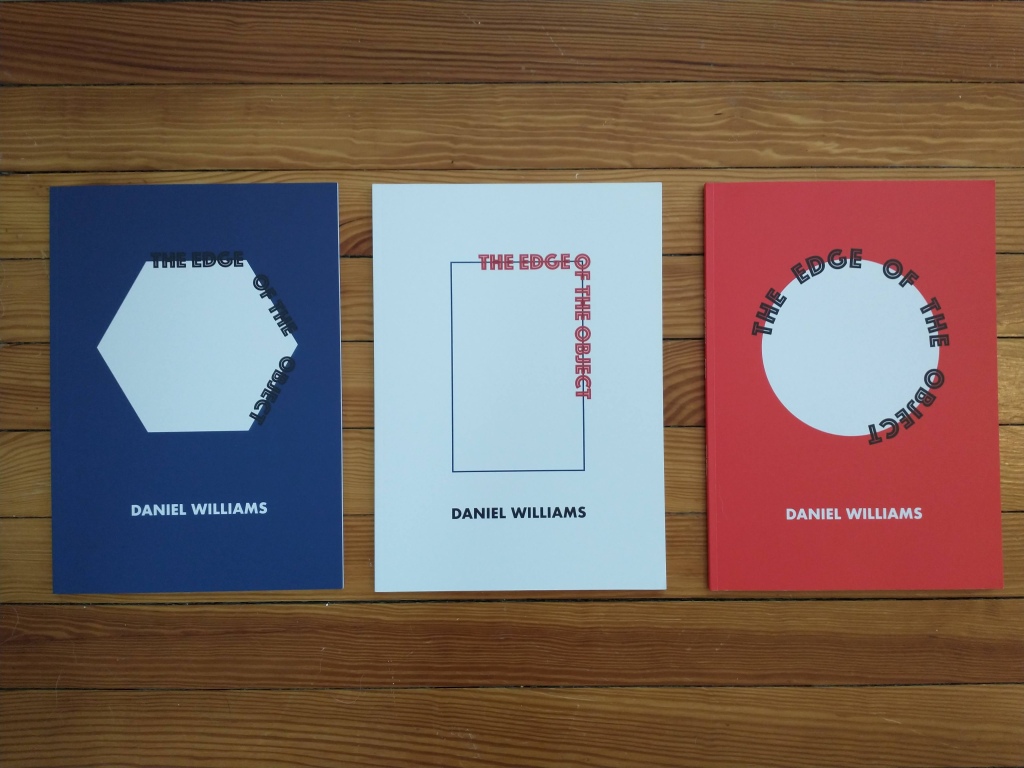

A tripartite journey—both geographical and emotional—Daniel Williams’s debut novel The Edge of the Object follows the highs and lows of a young Englishman living in France for a period of six months. The book as an object is striking to behold: three perfect-bound A4-sized volumes smartly dressed in the colors of the French flag and packaged in a screenprinted and letterpressed case—all designed and produced by Tim Hopkins of London’s The Half Pint Press. The prose found within is equally well crafted, with the book’s design complementing it nicely.

Taking cues in part from the work of Georges Perec, this novel is simultaneously a celebration of French culture as seen through the Francophilic eyes of a post-collegiate young man, and a keen look into the headspace of a person far from home, isolated by way of a language barrier he is only partly able to breach and yearning for human connections beyond what he often feels capable of. An erstwhile photographer, the unnamed narrator feels alternately liberated and hamstrung by the absence of his Leica—the camera offering a valid excuse to be present at a remove while also preventing true engagement in any given experience. This tension resulting from being camera-less clings to the narrative, as we watch the narrator struggle to engage with his surroundings—taking as many steps backward as forward in this endeavor—as he moves from place to place.

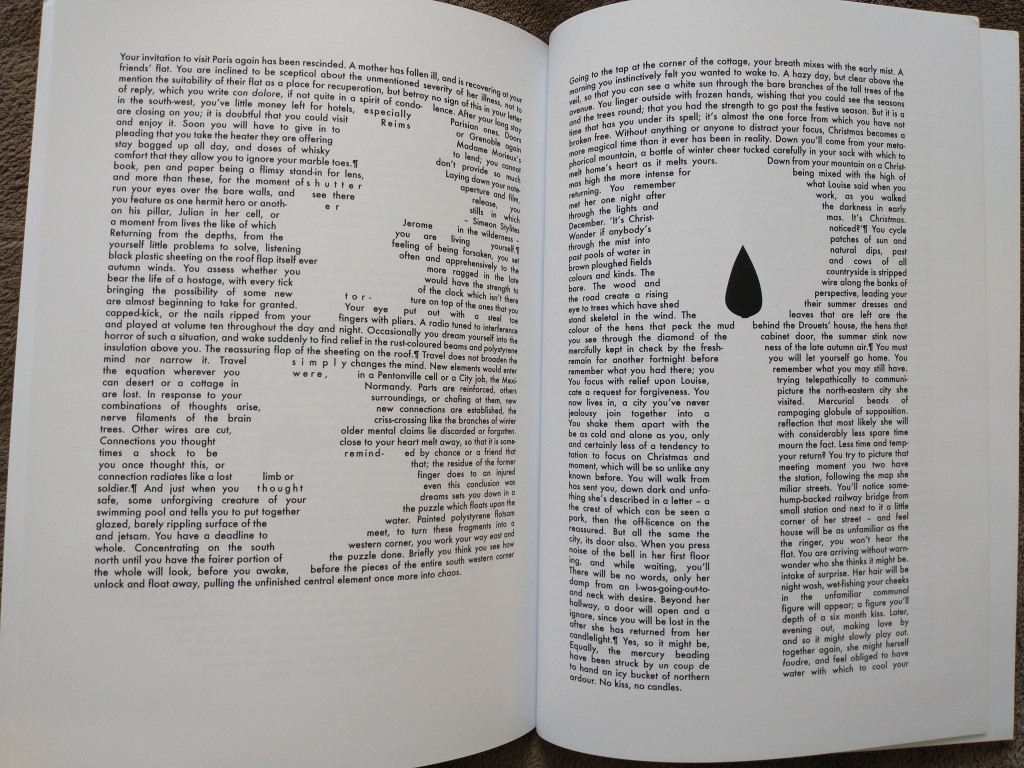

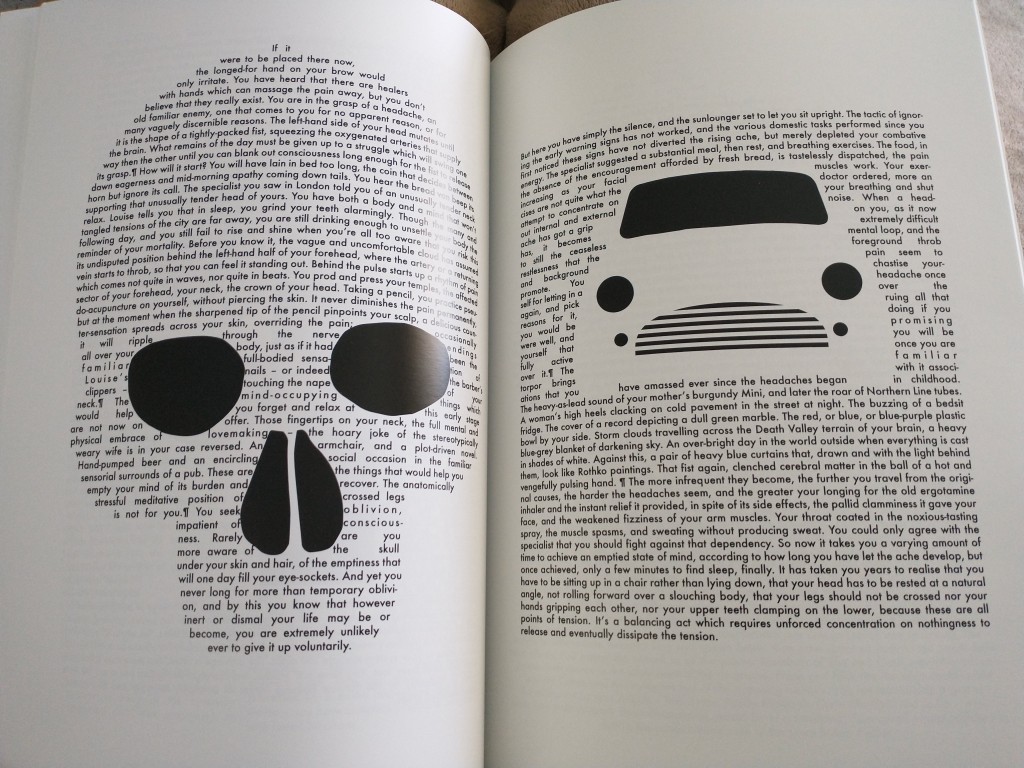

Williams writes with exacting precision—mapping the interior emotional journey of his narrator as carefully as he describes his geographical progress through France. He has a journalistic eye for detail, snapping word-images in lieu of photos and placing scene after scene in front of the reader with aplomb. Moments of wry humor and painterly passages of the French countryside counter the heaviness of themes of left-behind love and debilitating incidents of migraine headaches. Also tempering the at times somber subject matter, the pages of the first and third sections of the book are graced with striking calligrams—images sculpted from the words on the page and representative of a central theme or object on each page. These calligrams gently encourage the reader to slow down or speed up accordingly, keeping step with the pacing of the story.

The first part of the book is written in second-person point-of-view—unusual but appropriate to the experience of being in a rural area of a foreign country, surrounded by its natives, yet only with a workmanlike grasp of its language. The central character is living in a falling-apart cottage, not much more refined than a cave (and perhaps even less dry). Whenever nature calls, he must journey through a warren of gardens to reach the privy, and—adding to the inconvenience—the only running water for washing up is also located outside. It is hard living, made even harder by his isolation.

In the second part, the point-of-view segues to first person as our man reaches the big city of Paris and makes contact with the first of a series of friends he will spend time with over the coming weeks. Gone are the calligrams in favor of straightforward text blocks, as the focus in narration begins to point outwards in concert with the narrator’s efforts to interact more with the people around him. He soon meets up with a friend’s indie pop group on tour and joins them for a number of club dates around the country, during which he becomes interested in a woman whose feelings toward him are slippery at best.

The final part of the book returns to calligrams and the second-person distance, as the narrator backtracks to his lonely cottage existence. Here he comes to a decision about one last adventure to embark upon before his trip comes to a close. This jaunt provides a suitable denouement to his time in France, as we feel this fellow we’ve traveled so closely with start winding down and perhaps pine a bit harder for home. And indeed, the last page finds him back in England with his camera once again in hand—facing a future unknown but now fertilized with a rich new layer of experience from which to grow, perhaps out beyond the self he became too much of while away.

And yet, while these six months have taken you further from the excesses of the world than ever before, they have plunged you into an excess of time, of memory, and of yearning. If anything, you have become too much yourself.

[Limited print copies of the book may still be available, and the ebook has recently been released. Details at The Edge of the Object site. See also Williams’s essay in The Quietus on Perec’s novella A Man Asleep and its connection to this novel.]

1 Comment